I have been thinking a lot lately about names. In a language, names have a variety of ways they may manifest. Some are derived from older words in the language, some are identical to contemporaneous words, and some need certain morphology to indicate that they are, in fact, names, and not just regular words.

Rílin Given Names

In my various conlangs, I’ve taken different approaches to naming people. In Rílin, for example, there are specific name morphemes that mark a word as a person’s name. Some of these are gender specific, and some are gender neutral. Some have roots are traceable to either Rílin or Old Rílin words, but some do not have even discernable meaning. Below are some examples.

Feminine Names

Some feminine name suffixes include: -tót, -í, -u, -in/-ín, -ló

The following names are all derived from contemporary Rílin words, which become names with a suffix. (You can click on each name to hear it spoken.)

Bishéín [ˈbɪʃein] – from bishé ‘bright’

Esuí [ˈɛsui] – from esu ‘griffin’

Fylûlatót [fyˈlʌlatot] – from fylûla ‘bird’

Ítshaló [iˈtʃalo] – from ítsha ‘luck’

Kisin [ˈkɪsɪn] – from kis ‘honeybee’ or maybe kis ‘slender’

Mímin [ˈmimin] – from mím ‘cute, little’

Nesú [ˈnɛsu] – from nes ‘graceful’

| -tót | -í | -ú | -in/-ín | -ló | |

| bishé ‘bright’ | Bishéín | ||||

| esu ‘griffin’ | Esuí | ||||

| fylûla ‘bird’ | Fylûlatót | ||||

| ítsha ‘luck’ | Ítshaló | ||||

| mím ‘cute, little’ | Mímín | ||||

| kis ‘honeybee’ | Kisin | ||||

| nes ‘graceful’ | Nesú |

Not all Rílin names have clear or discernible meanings. They may still include some of the typical suffixes, but when detached from the rest of the word, that series of sounds does not necessarily make up a Rílin word.

Änsu [ˈænsu]

Äshtín [ˈæʃtin]

Alaí [ˈalai]

Bûlaísí [bʌˈlaisi]

Nímu [‘nimu]

Silin [ˈsɪlɪn]

Tsilu [ˈtsɪlu]

Tsheló [ˈtʃɛlo]

Masculine Names

Some suffixes are masculine, such as -n, -ó, -a, -ret.

Awun [ˈawun] – from awu ‘upright’

Bynóret [ˈbynoɾɛt] – from bynó ‘morning’

Daghóra [daˈɣoɾa] – from daghóra ‘sacrifice’

Evekaret [ɛˈvɛkaɾɛt] – from eveka ‘streak, brook’

Fífaía -[fiˈfaja] – from fífaí ‘advantage, benefit’

Gómó [ˈgomo] – from góm ‘thought, mind, know’

Kér̂a [ˈkeʂa] – from kér̂u ‘step forward, put (oneself) forward’

Some names may use naming suffixes but have indeterminate root meanings.

Ekhéla [ɛkˈhela]

Feneret [ˈfɛnɛɾɛt]

Gíŕan [ˈgiʐan]

Kedûn [ˈkɛdʌn]

Pirór̂nó [pɪˈɾoʂno]

Shíburet [ˈʃibuɾɛt]

Óŕina [oˈʐɪna]

Gender Neutral Names

Other name suffixes are gender neutral, such as -ja, -bí, and -tos. These could be used for a person of any gender. Some of these names are very old and no longer have clear roots.

Béíntos [ˈbeintɔs] – unknown root

Ískesébí [iskɛˈsebi] – from ískesé ‘high, tall’

Jenja [ˈjɛnja] – probably from jen ‘day’

Kótos [ˈkotɔs] – maybe from kó ‘intention, meaning’

Other names may not include a suffix at all. Most of these names can be used regardless of gender.

Amlim [ˈamlɪm]

Köle [ˈkølɛ]

Ŕetsŭ [ˈʐɛtsɯ]

Nemne [ˈnɛmnɛ]

Valhén [ˈvaɬen]

Rílin Family Names

Rílin family names come after given names. Names are inherited by children from their parents. Female children inherit their mother’s name, and male children their father’s name (typically, although there are exceptions to this). Therefore, they are somewhat matronymic and patroymic in function, although they also act as family names since there is no other inherited name for most Rílin people.

For example, Silin, a middle-aged Rílin woman, would have her mother’s last name, Bízunla. Her husband, Nósh, would have his father’s name, Ínómí. Their son would take his father’s name too. Family names often concern personal traits, origins, trades, and skills. Bízunla comes from bízun ‘alarm, alert’, with a possible agentive suffix -la. So the original meaning might have been “one who warns or foretells”. Ínómí looks like the word ínó ‘color’ plus a genitive suffix –mí, so might mean “with color, of color”. This could either have originally referred to a personal trait (some color of the body–hair, eyes, skin, or even clothing) or it could have referred to a colorful place of origin, like a green forest or floral garden, etc.

These are just a few points concerning Rílin naming conventions. In the future, I will write a bit about Rílin nicknames as well as expand on naming conventions of other cultures across Aeniith. Thanks for reading!

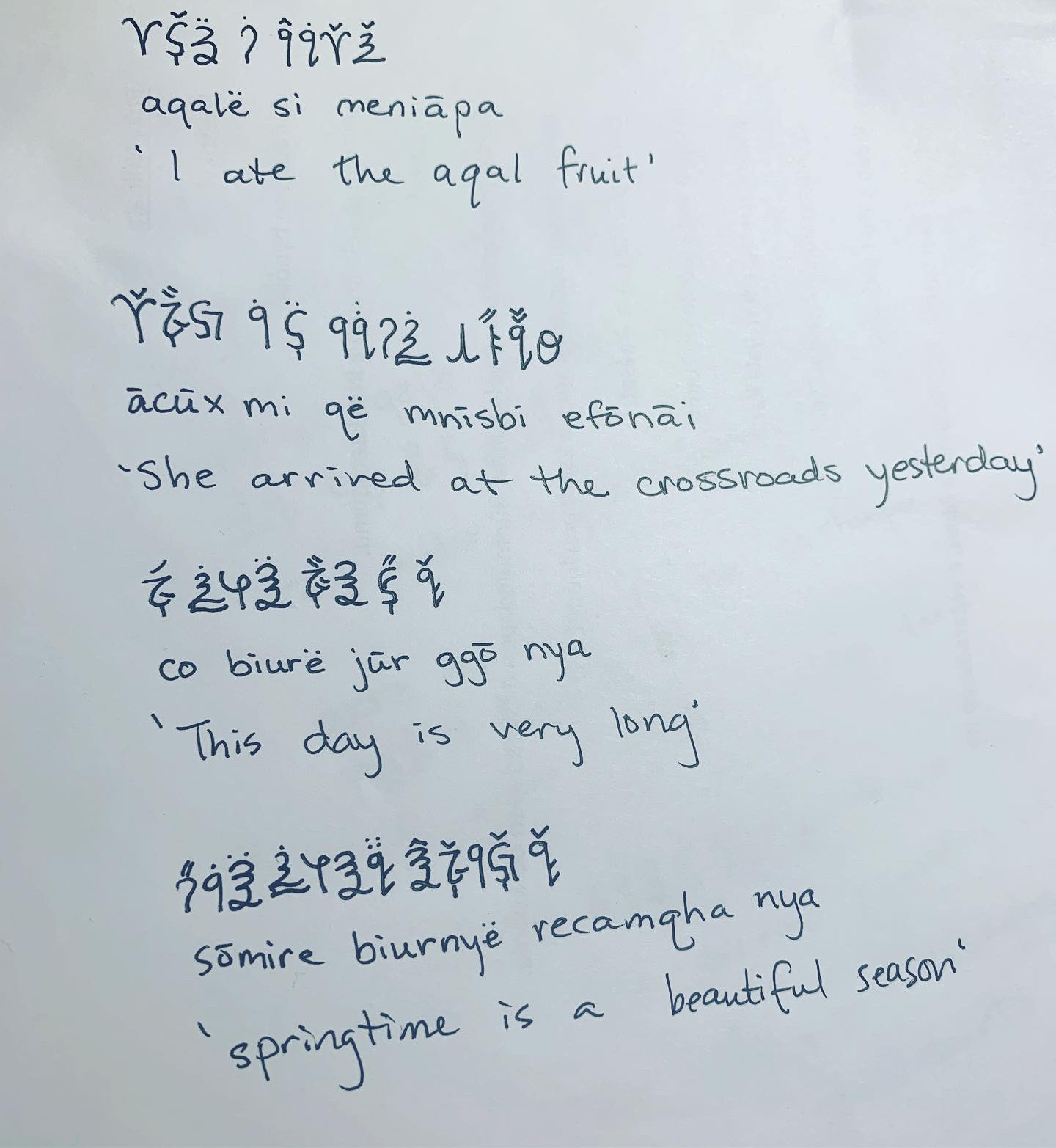

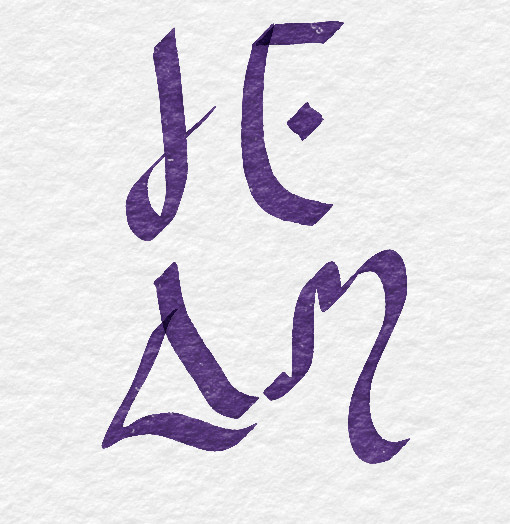

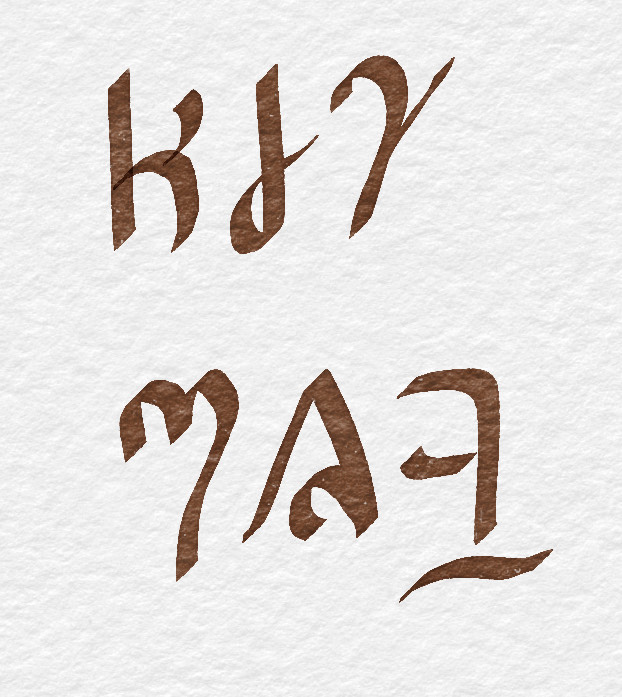

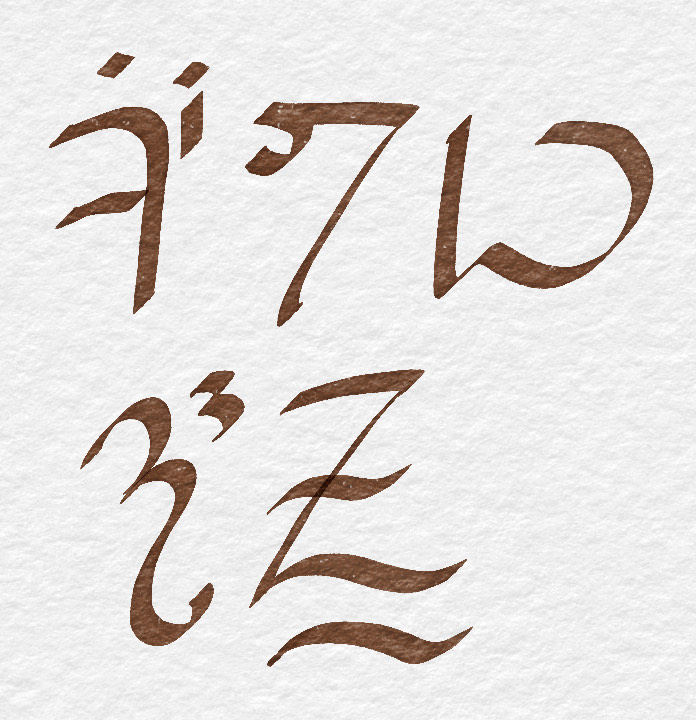

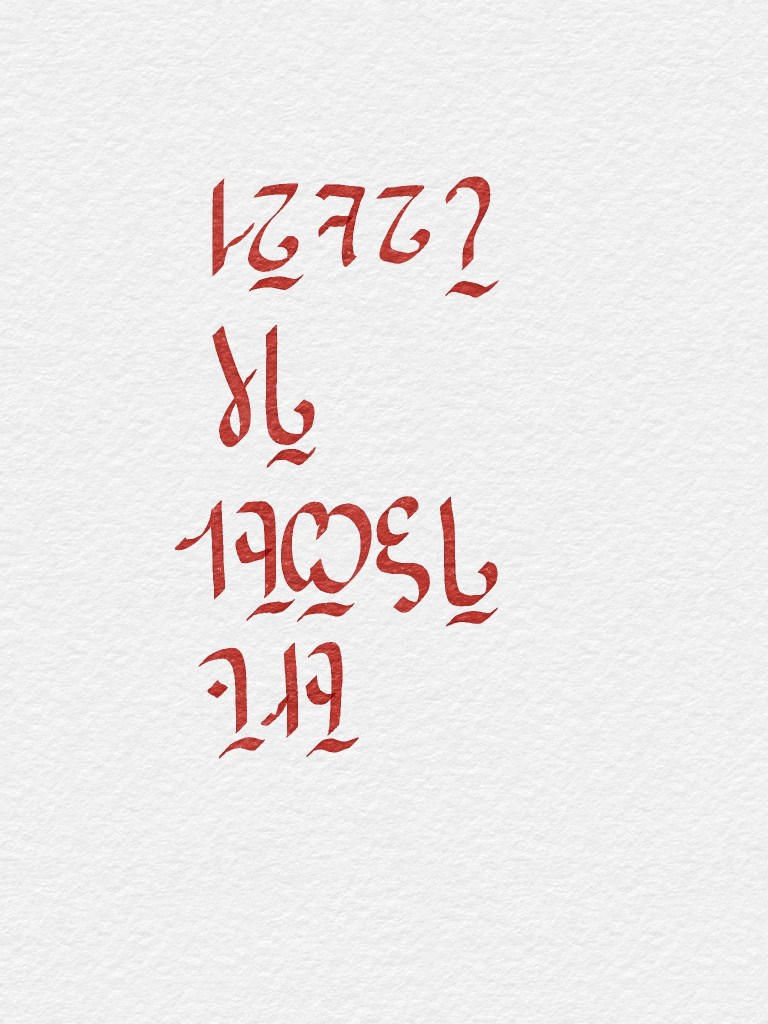

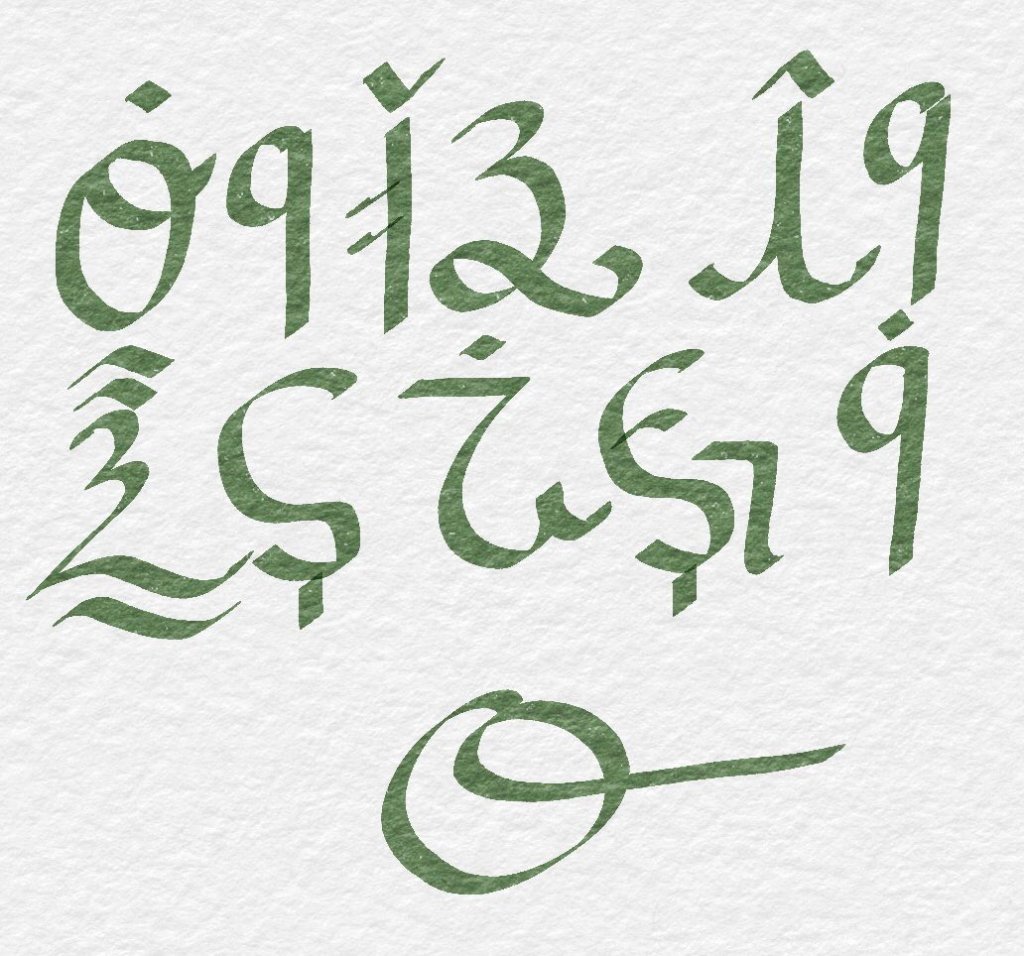

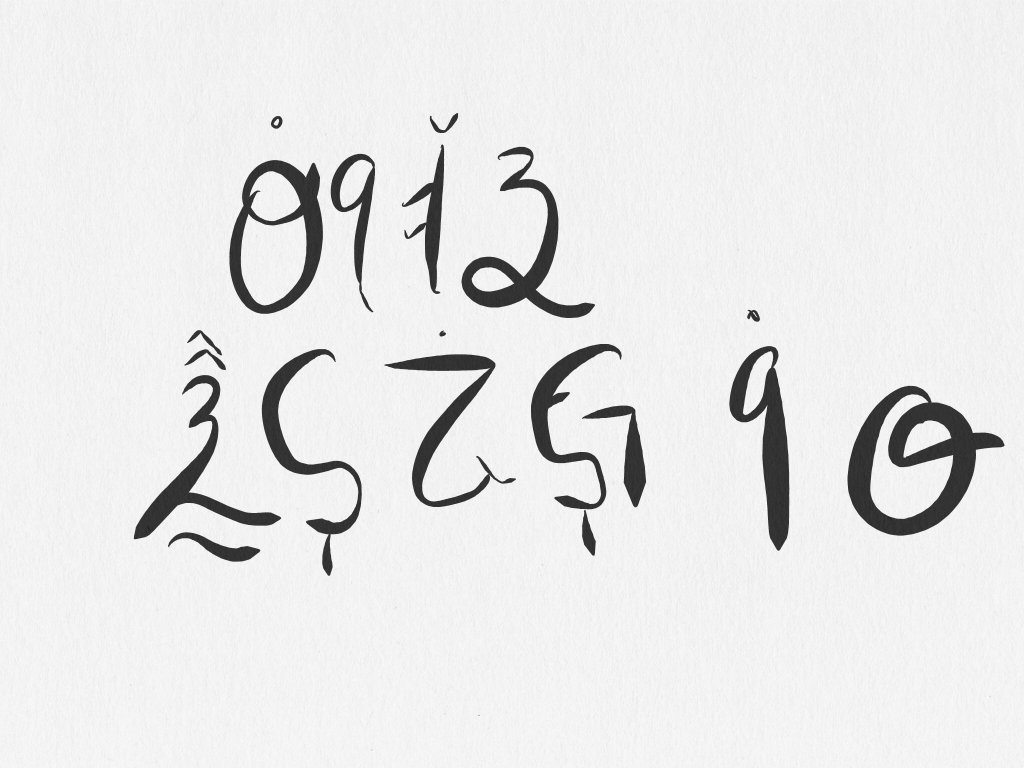

Each consonant is a full letter with the following vowels being marked as diacritics over the consonant. Freestanding vowels are written as full, and diphthongs and double vowels are either combined diacritics or a full vowel symbol plus a diacritic.

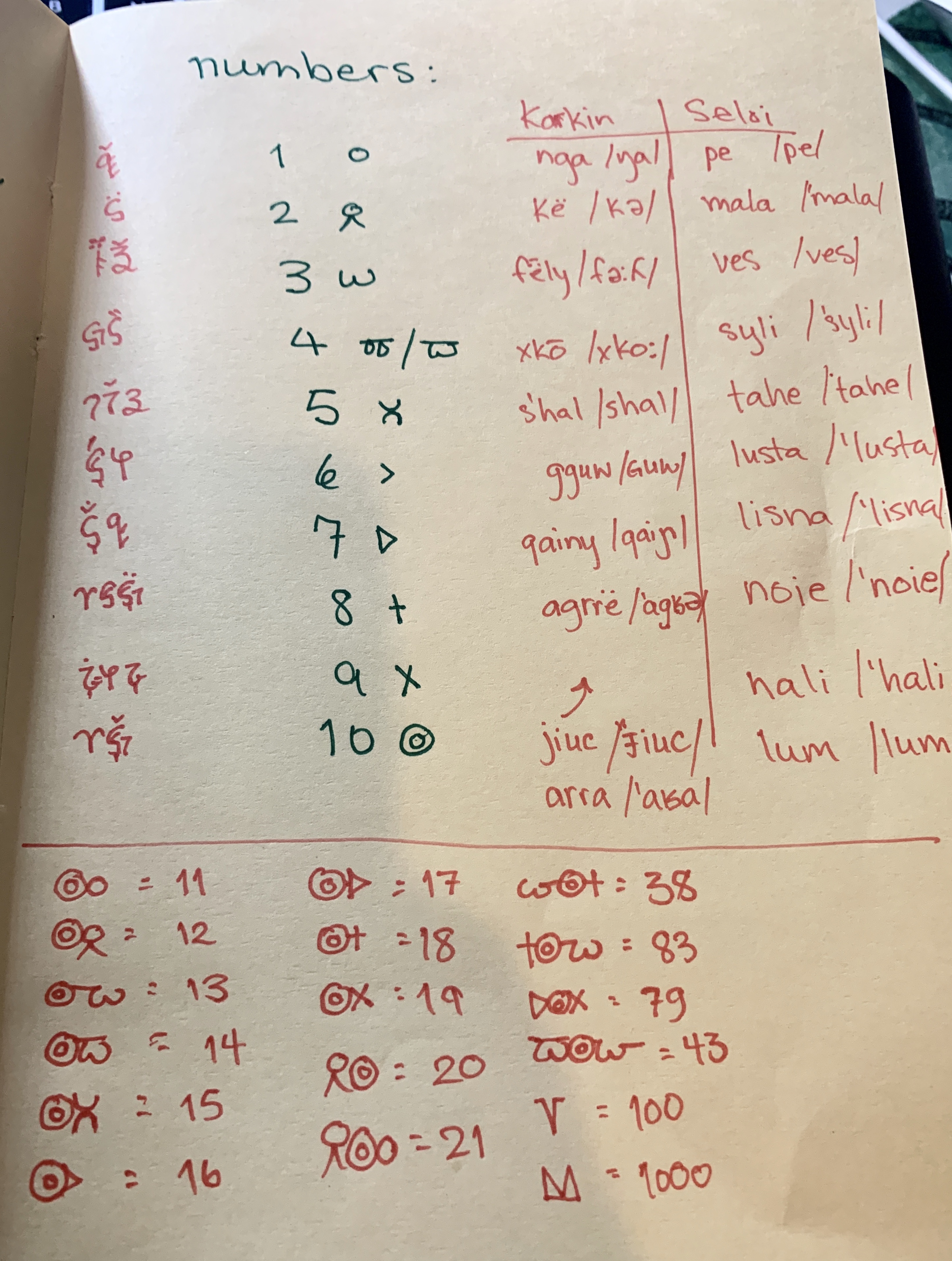

Each consonant is a full letter with the following vowels being marked as diacritics over the consonant. Freestanding vowels are written as full, and diphthongs and double vowels are either combined diacritics or a full vowel symbol plus a diacritic. As you can see, many letters are modified to represent the numerous additional sounds that Karkin has. Some consonants have added marks to indicate that voicing (Seloi doesn’t have voiced stops like b, d, g, for example). Some letters have descender marks below them to indicate a change in place of articulation (usually farther back in the mouth). Some fricatives (like the letters for v and s) are reversed to show a change in voicing (f and z). The letter for /l/ is modified to represent /r/ and /ʎ/. Various other changes show sounds that don’t exist in Seloi. Long vowel are represented by double diacritics.

As you can see, many letters are modified to represent the numerous additional sounds that Karkin has. Some consonants have added marks to indicate that voicing (Seloi doesn’t have voiced stops like b, d, g, for example). Some letters have descender marks below them to indicate a change in place of articulation (usually farther back in the mouth). Some fricatives (like the letters for v and s) are reversed to show a change in voicing (f and z). The letter for /l/ is modified to represent /r/ and /ʎ/. Various other changes show sounds that don’t exist in Seloi. Long vowel are represented by double diacritics.